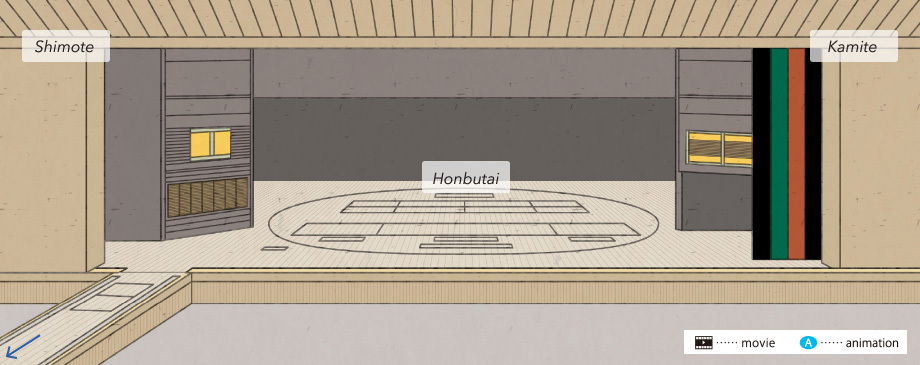

The Stage

Like many theatre productions around the world, staging is a key aspect of kabuki shows. Different areas of the stage contain both narrative and practical significance. The kamite area is the right side of the stage when viewed from the audience. It is generally staged for indoor scenes and for characters of higher status. In most cases, it is understood as the East. The shimote area is the left side of the stage when viewed from the audience. It is generally staged for outdoor scenes and for characters of lower social rank. It is understood as the West. The audience would be the South.

In the center of the stage is the mawaributai or revolving stage. It is a rotating section of the stage that allows for quick set and scene changes, usually in full view of the audience. This adds to the show's visual appeal as well as practicality. The mawaributai was introduced to kabuki in the latter half of the Edo Period and quickly became a kabuki staple. The idea of a rotating stage spread outside of Japan during the Meiji Era.

The seri is the stage elevator located in the center of the stage with the mawaributai. It is used to raise and lower set pieces, actors, and parts of the stage. Again, these transitions happen in view of the audience. The seri is accessed from the naraku, the below-stage basement. The naraku is the area(s) under the main stage where the mawaributai and seri are installed and managed. When it was first used, the area under the stage was often dark and damp, so it was named "naraku" which means "hell."

The kuromisu is the musicians' room. It is located on the shimote side of the stage and used for nagauta music (singing to shamisen accompaniment), taiko (stick drum), tsuzumi (shoulder drum) and other sound effects. This area is called kuromisu or geza because both words refer to the music used in kabuki.

Pictured above: a kuromisu

The yuka is the narrator's area. It is located on the kamite side of the second floor. The narrator will narrate from a small room.

The joshiki-maku is the curtain at the very front of the stage. Its purpose is similar to that of a red curtain used in Western theatre: to signify the beginning or end of a scene or act. Unlike curtains in Western theatre, the joshiki-maku is made of colorful strips of fabric that are black, dark green, and orange. The curtain closing is also accompanied by sound of hyoshigi (wooden clappers).

Pictured above: a joshiki-maku

Perhaps the most notable feature of any kabuki stage is the hanamichi, or the walkway that extends from the shimote side of the stage through the audience and ends in a small room at the back of the theatre. The hanamichi can function as whatever the scene requires of it, be that a corridor, bridge, road, riverbank, ocean, or something else. It is a helpful tool that intensifies the connection between the actors and audience members. Some theaters have a second hanamichi on the kamite side.

Many kabuki theaters have a second, smaller stage elevator called a suppon used to raise and lower part of the hanamichi near the stage. This smaller seri is often utilized for entrances of characters such as ghosts, spirits, sorcerers, goblins, and other supernatural beings to give the illusion that they have suddenly appeared. Sometimes these entrances are accompanied by smoke or fog. Like the main seri, actors access the suppon from the naraku. This elevator got its name because the entrances reminded audiences of a turtle thrusting its head out of its shell.

Finally, at the end of the hanamichi hangs the agemaku, or entrance curtain. This curtain marks the separation between the room at the end of the hanamichi and the audience seating. Actors use this room for dramatic entrances and exits through the audience.

Pictured above: an agemaku